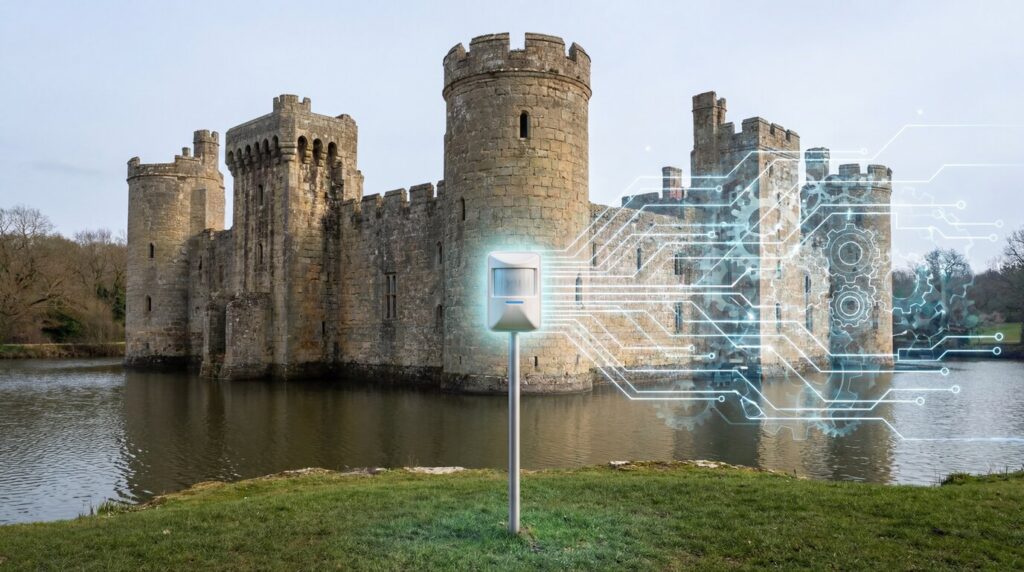

From Moats to Motion Sensors: Re-thinking Defensibility When Every Product Ships with an API and Your Competitor Is an Open-Source Side Project

For much of modern business history, defensibility was imagined as a structure. Leaders spoke in architectural metaphors: moats, walls, barriers to entry. Strategy decks highlighted proprietary technology, patents, exclusive partnerships, distribution control, and switching costs. The goal was to build a position so hard to replicate that competitors would be discouraged before they even tried.

That logic still appears in boardrooms. But it increasingly fails to explain what actually happens in contemporary technology markets—especially those shaped by APIs, cloud infrastructure, and open source. Today, competitors do not need to breach the wall. They can route around it. They can integrate, fork, wrap, or reassemble what already exists. They can emerge from a GitHub repository, not a venture-backed startup.

In this environment, defensibility no longer behaves like a static asset. It behaves like a capability. Advantage is less about what you own and more about how quickly you sense change, how effectively you respond, and how reliably you operate once embedded. The metaphor shifts from moats to motion sensors.

Motion sensors do not stop intruders on their own. They detect movement early, reduce surprise, and enable rapid response. They assume the perimeter is porous. That assumption increasingly matches reality.

This essay examines why traditional moats erode faster in API-first, open-source-heavy markets, what forms of defensibility still compound, and how leaders—across enterprises, consultancies, and startups—should adapt their strategic posture.

Why Traditional Moats Are Under Pressure

The Product Boundary Has Collapsed into an Interface Boundary

In API-first markets, customers rarely experience software as a monolith. They experience it as a set of callable capabilities embedded into workflows, pipelines, and automations. Value is delivered through integration, not installation.

This matters because interfaces are inherently substitutable. If two products expose similar APIs, switching no longer requires ripping out a system; it requires re-wiring a connection. The friction shifts from organizational change to technical compatibility. As standards mature and SDKs proliferate, even that friction declines.

For enterprise buyers, this reframes evaluation criteria. The question becomes less “Which product is best?” and more “Which interface can we standardize, govern, and trust at scale?” Feature depth still matters, but reliability, predictability, and control increasingly dominate decisions.

In this world, differentiation must show up where interfaces meet operations: latency consistency, error handling, versioning discipline, backward compatibility, and developer experience. These are not traditional moat attributes, but they determine who becomes the default dependency.

Open Source Compresses the Time to Competition

Open source is no longer a niche tactic. It is the substrate of modern software. Most enterprise applications are composites of open components maintained by global communities.

That reality changes competitive dynamics in two important ways.

First, it accelerates innovation. Ideas propagate quickly. Patterns stabilize faster. Best practices become visible. Second—and more strategically—it compresses the time it takes for alternatives to become viable.

When a category is anchored to an open core, a competitor does not need to invent functionality from scratch. They can fork, extend, or package what already exists. Under the right conditions—licensing shifts, governance disputes, ecosystem dissatisfaction—those forks can attract serious momentum.

Recent history illustrates the pattern clearly. Infrastructure, data platforms, and developer tooling have all seen credible alternatives emerge rapidly from community efforts once trust in a steward weakened or terms changed. The lesson is not that open source is dangerous. The lesson is that forkability is real, and it reduces the half-life of purely technical advantage.

For vendors, this means that owning the code is rarely sufficient. For buyers, it means that vendor lock-in is less absolute than it once appeared—and operational burden fills the gap.

Static Assets Can Become Strategic Liabilities

Many organizations still treat defensibility as something to accumulate: more IP, more complexity, more internal differentiation. In API-first environments, those same assets can slow response.

When markets move quickly, the speed of adaptation matters more than the uniqueness of components. If your architecture, governance model, or release process makes change difficult, your “moat” becomes a drag on your business. Competitors that assemble faster—even from shared parts—can outrun you.

This dynamic is visible in how enterprises now think about risk. Open-source use is widespread, but so are concerns about supply chain security, licensing exposure, and operational resilience. Leaders increasingly recognize that speed without control is unsustainable. The strategic question becomes: who absorbs complexity, and who absorbs risk?

Vendors that push risk downstream to customers—by offering raw components without operational guarantees—may win early adoption but struggle in regulated or mission-critical environments. Vendors that internalize complexity and surface assurance gain staying power.

Innovation Has Shifted to Ecosystems and Learning Loops

The pace of experimentation in modern software ecosystems is extraordinary. Thousands of new projects, wrappers, and integrations appear every month. Generative AI, automation frameworks, and agent tooling have amplified this effect, further lowering the cost of exploration.

In such an environment, no single organization can monopolize innovation. Advantage accrues to those who can absorb external ideas, integrate them responsibly, and translate them into reliable outcomes.

This is where static moats fail. You cannot wall off an ecosystem. You can, however, orchestrate it. That orchestration—deciding what to adopt, what to harden, what to expose, and what to constrain—is a dynamic capability. It depends on sensing weak signals early and acting before they become obvious.

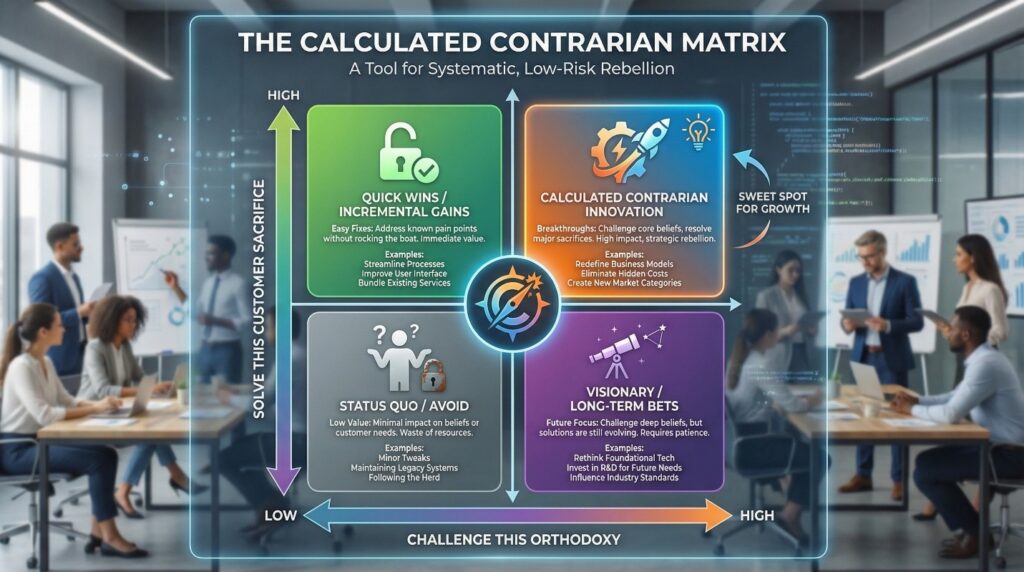

The New Defensibility Stack: What Still Compounds

If defensibility is no longer primarily about exclusion, what replaces it? The answer is not a single factor but a layered stack of advantages that reinforce one another over time. Each layer is harder to replicate quickly, even when the underlying code is visible.

Trust as a First-Class Product Capability

In enterprise contexts, trust is operational, not emotional. It is expressed through controls, guarantees, and repeatability.

Trust shows up in audit logs that actually answer questions. In access models that enforce least privilege by default. In deterministic behavior where required, and transparent nondeterminism where allowed. In clear lines of accountability, when something goes wrong.

As competitors converge on features, trust becomes the attribute customers are least willing to experiment with. Few executives will risk production systems, regulatory exposure, or reputational damage to save marginal cost. Products that bake trust into their core—rather than selling it as a service add-on—build inertia that compounds.

A useful test for leaders is simple: if your product vanished overnight, could a customer replicate the same risk posture using open alternatives within a month? If the answer is yes, defensibility is weak. If the answer is no because of embedded governance, assurance, and operational maturity, the advantage is real.

Workflow Embedding as Behavioral Switching Cost

Traditional switching costs were contractual and financial. Modern switching costs are behavioral.

When a product becomes the default way work gets done—how tickets are created, how decisions are approved, how processes are monitored—it shapes habits. Those habits persist even when alternatives exist.

APIs amplify this effect. Once your system is embedded in automation, runbooks, or agent workflows, replacing it requires redesigning how work flows through the organization. That is far harder than migrating data or renegotiating contracts.

This kind of defensibility is subtle but powerful. It does not rely on exclusivity. It relies on becoming invisible infrastructure.

Data Advantage Reframed as Learning Velocity

The phrase “data moat” is often misleading. Data itself is rarely scarce. What is scarce is the ability to turn data into sustained improvement.

Defensibility emerges from closed loops: instrumentation feeding insight, insight driving change, change producing outcomes, and outcomes refining instrumentation. When these loops are tight and domain-specific, they compound quickly.

Competitors can copy models and architectures. They cannot instantly copy how your system learns in production, especially when that learning is embedded in customer-specific workflows and constraints. Over time, this creates divergence that is difficult to bridge.

This is motion-sensor defensibility in action. You are not protecting a static asset. You are protecting a process that keeps moving ahead.

Distribution That Rides Standards Without Becoming Fragile

Standards lower barriers to entry, but they also create default paths. In API-driven markets, the easiest integration often becomes the safest choice.

Developer experience matters here more than branding. Clear documentation, stable interfaces, sensible defaults, and strong tooling can make one option feel “obvious.” Once that perception sets in, it influences procurement and architecture decisions far beyond the developer team.

The strategic goal is not to fight standards but to align with them so well that your product becomes the reference implementation. That position can be surprisingly durable, even when alternatives are technically comparable.

Operational Excellence at the Interface Level

As categories mature, differentiation shifts from novelty to reliability. In production environments, consistency matters more than capability.

Service-level objectives, incident response discipline, upgrade predictability, and edge-case handling determine whether a product is trusted as infrastructure or treated as an experiment. These attributes are expensive to build and slow to copy.

Open-source side projects can quickly match features. They rarely match operational maturity at scale. Vendors that invest here create a widening gap over time.

What “Motion Sensors” Look Like Organizationally

Accepting that defensibility is dynamic requires changes in how organizations operate, not just what they build.

Instrument the Market, Not Just the Product

Most companies have detailed telemetry on product usage. Far fewer have systematic visibility into ecosystem signals: forks gaining traction, maintainers disengaging, standards coalescing, or new abstractions emerging.

Motion-sensor organizations treat these signals as operational data. They monitor repositories, communities, dependency graphs, and integration patterns with the same seriousness they apply to customer metrics. The goal is early awareness, not perfect prediction.

Plan for Forks and Substitution Before Crisis

Forks are no longer edge cases. They are part of the strategic landscape. Both vendors and buyers should assume that key components may change stewardship or fragment.

For vendors, the response is not legal defensiveness but strategic differentiation above the fork line: managed experience, compliance posture, ecosystem integration, and accountability.

For buyers, the response is architectural optionality: understanding where substitution is acceptable and where assurance is non-negotiable.

Treat API Strategy as Automation and AI Strategy

As automation and AI agents become primary consumers of APIs, interface design becomes a governance issue. APIs must encode policy, enforce constraints, and produce traceable outcomes.

Defensibility here comes from making automation safe by default. Organizations that treat APIs as mere transport layers will struggle. Those who treat them as decision boundaries will earn trust.

Turn Supply Chain Assurance into Advantage

Software supply chain risk has moved from a technical concern to a board-level issue. Organizations increasingly expect vendors to provide transparency, provenance, and controls out of the box.

Products that reduce audit burden, simplify compliance, and make risk legible gain disproportionate influence. In many deals, the security and risk review is the real competition.

Implications for Founders and Enterprise Leaders

For Founders

Code is cheap. Outcomes are not.

Founders should push differentiation into the last mile: onboarding speed, safety, governance, and measurable impact. The goal is not to out-innovate the ecosystem but to out-integrate and out-operate it.

Open source can accelerate adoption, but the strategic core should remain in orchestration, assurance, and learning loops. The defensible system is not the algorithm; it is the disciplined machinery around it.

For Enterprise Leaders

The build-versus-buy debate has shifted. The question is no longer where software is cheaper, but where risk should reside.

Open components are appropriate where commoditization is acceptable and internal capability exists. Managed platforms are appropriate where failure is expensive and accountability matters.

The critical discipline is clarity: knowing which layers of your stack are strategic dependencies and which are interchangeable parts.

A Practical Checklist for Monday Morning

- Which parts of our product or stack are easily forkable primitives, and which are compounding systems?

- Do we measure operational reliability as a competitive metric rather than just an internal one?

- Could a motivated team replace us—or our vendor—with open components in 90 days? What would stop them?

- Are our APIs governable enough for automation and agents?

- Do we have a structured way to sense ecosystem shifts before they become obvious?

Think:

Defensibility has not disappeared. It has migrated.

In a world where every product ships with an API and every category casts an open-source shadow, advantage no longer lives primarily in walls and patents. It lives in motion: the ability to sense change early, respond decisively, and operate with a level of trust that competitors cannot easily replicate.

The winners will not be those who build the tallest moats. They will be those who install the best sensors—and build organizations capable of acting on what those sensors detect.