The Adjacency Conquest: How Market Leaders Build Compound Moats Through Systematic Layer Expansion

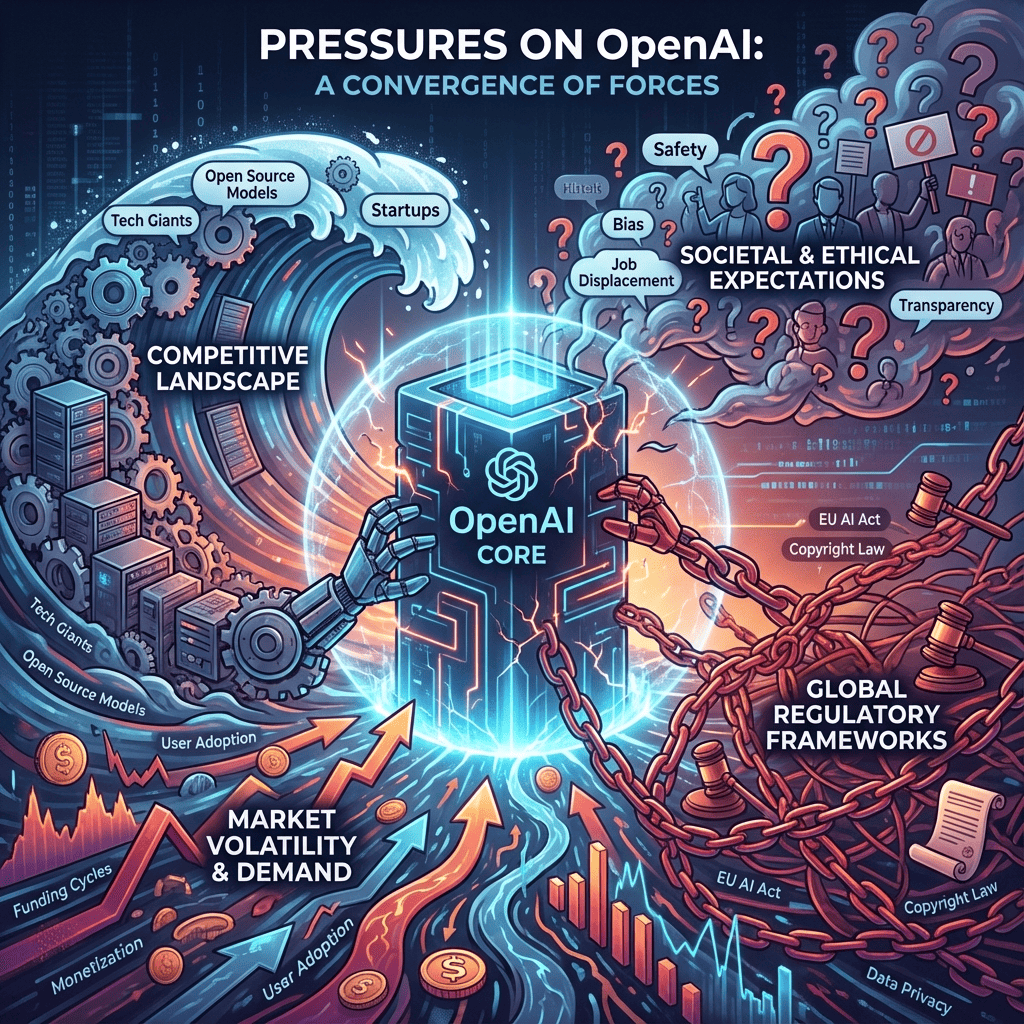

Sarah Chen stared at the quarterly board deck, trying to explain why their best-in-class CRM was losing enterprise deals to Salesforce—again. “We have better uptime, faster implementation, and our AI features shipped six months before theirs,” she said. The problem wasn’t her product. It was that Salesforce no longer sold CRM. They sold CRM, analytics, marketing automation, commerce, and Slack. They’d stopped competing on features and started competing on surface area.

This is the adjacency trap that kills category leaders. You perfect your core while a competitor quietly assembles a constellation of capabilities around it. By the time you notice, they’re not just ahead—they’re unreachable. The game changed, and you’re still playing checkers.

Download: Two Ready-to-Use Strategic Tools

Adjacency Expansion Readiness Scorecard

The Adjacency Stack Mapping Worksheet

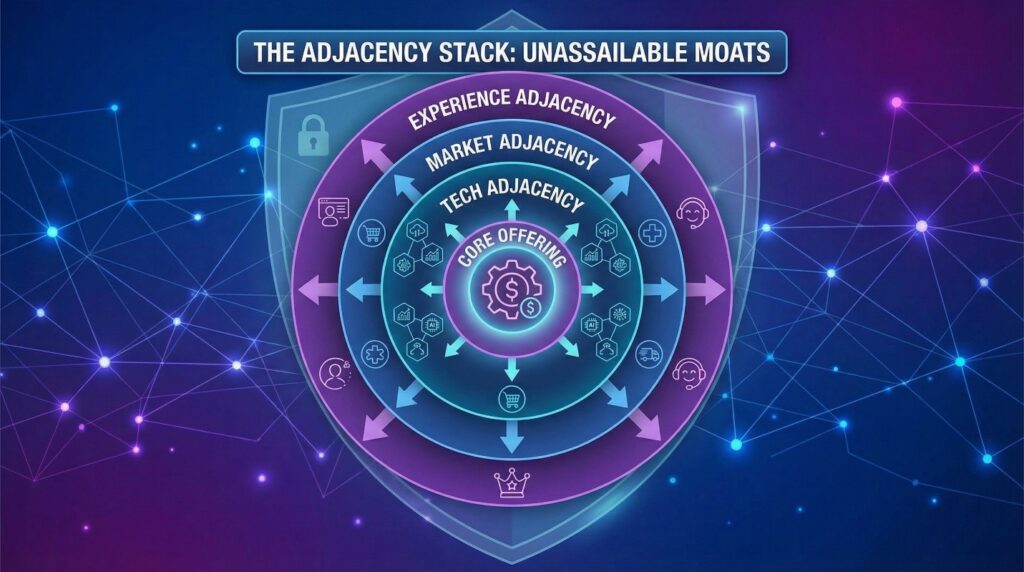

The Adjacency Stack: A Framework for Systematic Market Domination

The Adjacency Stack maps how dominant players systematically expand beyond their core offering to create what I call compound moats—defensive positions that multiply in strength because each layer reinforces the others. This isn’t about product sprawl or unfocused diversification. It’s about strategic accretion guided by a rigorous logic of customer workflows, data gravity, and switching-cost amplification.

Think of it as a three-dimensional pyramid:

Layer 1: The Defended Core — Your primary value proposition, hardened against direct competition through technical excellence, brand, or network effects.

Layer 2: Natural Adjacencies — Capabilities that share the same customer, data substrate, or workflow context. These feel like logical extensions to users.

Layer 3: Strategic Adjacencies — Moves that seem tangential but control critical inputs, distribution channels, or complementary experiences.

Layer 4: Ecosystem Lockup — Platform features, developer tools, and integration standards that make your stack the gravitational center for third parties.

The power emerges from vertical integration across these layers. Each new capability increases the cost of switching, creates proprietary data feedback loops, and raises barriers for single-point competitors. Amazon didn’t dominate retail by having the best product search. They layered Prime membership on logistics, AWS, seller services, and payment infrastructure. Each addition made the previous layers stickier.

Mapping the Stack: How It Actually Works

Let’s examine Microsoft’s systematic conquest of the enterprise productivity market—a masterclass in adjacency stacking that transformed it from a “Windows company” into a “work infrastructure provider.”

Layer 1 (Defended Core): Office suite dominance. By 2005, Word, Excel, and PowerPoint were entrenched through file format lock-in and muscle memory. But Google Docs was gaining ground with collaboration features that Microsoft didn’t have.

Layer 2 (Natural Adjacencies): Rather than improve Office, Microsoft asked: “What else happens in the same workflow context?” The answer: email, calendaring, file storage, video calls. They bundled Exchange, SharePoint, OneDrive, and later Teams into Office 365. Suddenly, buying best-of-breed tools meant managing five vendor relationships instead of one.

Layer 3 (Strategic Adjacencies): Azure integration wasn’t apparent in 2010. Why does a productivity suite company need cloud infrastructure? Because enterprise IT buyers make bundled decisions. The CIO evaluating Office 365 is the same person procuring cloud compute. Microsoft could now offer: “Run your apps on Azure, manage them through our admin tools, secure them with our identity layer, and your employees can access everything through Office.” That’s not a product pitch—it’s a nervous system for the enterprise.

Layer 4 (Ecosystem Lockup): Microsoft Graph API, Power Platform, Teams app framework. Third-party developers now build on top of Microsoft’s stack, not alongside it. Every integration reinforces Microsoft as the central hub.

The result? Microsoft 365 has 345 million paid seats. Slack had 18 million daily active users when it was acquired by Salesforce, for a product many considered superior to Teams. The adjacency stack made product quality almost irrelevant at scale.

The Mechanism: Why Adjacency Stacks Multiply Defensive Strength

Traditional moats—brand, network effects, economies of scale—operate in isolation. The adjacency stack creates moat multiplication through three compounding mechanisms:

- Data Gravity Amplification

Each layer generates proprietary data that enhances the others. Shopify’s payment processing (Shopify Payments) feeds transaction data into capital lending (Shopify Capital), which improves merchant retention modeling and, in turn, refines their point-of-sale hardware recommendations. A payments-only competitor sees transaction flow. Shopify sees merchant health, inventory turns, cash flow stress, and expansion readiness. That intelligence compounds with every added layer.

- Switching Cost Triangulation

Users tolerate mediocrity in individual features when the combined switching cost becomes prohibitive. Apple’s ecosystem illustrates this perfectly. Is iMessage the best messaging app? Debatable. Is the Apple Watch the best wearable? Maybe not. Are AirPods the best earbuds? Plenty of alternatives. But the interoperability tax of leaving—losing seamless device handoff, shared photo libraries, iMessage group chats, watch-phone integration—is existential. You’re not switching products; you’re switching identities.

- Cross-Subsidy Economics

Dominant layers fund aggressive investment in emerging ones. Amazon ran AWS at a loss for years, subsidized by retail margins. Google offers Gmail and Drive for free because search advertising funds them. This creates an asymmetric battlefield: specialists must price for profit on every product while stack players can weaponize free tiers to acquire users, then monetize through upsell into premium layers.

Here’s the kicker: these mechanisms create emergent defensibility. Stripe started as a payment processing company. Reasonable moat. Added fraud detection (Radar), business banking (Treasury), revenue recognition (Billing), corporate cards (Issuing), and identity verification (Identity). Now they’re not a payments company—they’re a financial infrastructure layer that happens to start with payments. The combined stack is nearly impossible to displace, as pulling on one thread unravels the entire workflow.

Practical Implementation: The Adjacency Conquest Playbook

Most companies approach adjacencies opportunistically: “Our customers asked for it” or “We have spare engineering capacity.” That’s how you get feature bloat, not compound moats. Systematic adjacency stacking requires disciplined sequencing.

Step 1: Map Your Customer’s Full Job-to-be-Done

Don’t ask what adjacent products you could build. Ask what adjacent problems exist in the same customer workflow. Figma started with interface design but mapped the complete design-to-development handoff: whiteboarding, prototyping, design systems, developer handoff, and design asset management. Each became a layer.

Workshop question: “When our customer finishes using our product, what do they do in the next 10 minutes? What about the previous 10 minutes?” Those boundary moments reveal natural adjacencies.

Step 2: Identify Your Proprietary Data Advantage

Build adjacencies that leverage your existing data to create unfair advantages. Netflix moved from streaming to production because its viewing data told it exactly what shows would succeed—before shooting a pilot. That’s strategic adjacency: the core business generates intelligence that incumbents in the new layer (traditional studios) don’t have.

Red flag: If your proposed adjacency doesn’t benefit from data you uniquely possess, you’re just entering a new market. That’s fine, but it’s not stacking.

Step 3: Sequence by Switching Cost Addition

Prioritize adjacencies that multiply exit friction. HubSpot layered CRM on top of marketing automation, then added sales, service, CMS, and payments tools. Each addition created new data dependencies and workflow integration. Ripping out HubSpot now means:

- Migrating contact databases (CRM)

- Rebuilding email automation sequences (Marketing Hub)

- Reconfiguring sales pipeline triggers (Sales Hub)

- Transferring service ticket history (Service Hub)

- Redesigning website infrastructure (CMS Hub)

- Switching payment processors (Payments)

That’s not a vendor swap; it’s a systems migration project that requires executive sponsorship and board approval.

Step 4: Build Ecosystem Leverage Before Direct Competition

The mistake: immediately competing head-to-head with incumbents in your target adjacency. The strategic move: create integration and API infrastructure that makes you indispensable, then launch your own version.

Stripe did this brilliantly. They integrated with every fintech tool before building competing products. By the time Stripe launched corporate cards (competing with Brex, Ramp), revenue recognition software (competing with Zuora), and fraud tools (competing with Sift), they were already embedded in those companies’ infrastructure. Partners had to decide: keep using our API while we compete with you, or rip out foundational infrastructure. Most chose coexistence.

Step 5: The Anti-Sprawl Filter

Not every adjacency strengthens the stack. Test each potential layer against three criteria:

- Shared Data Substrate: Does this layer generate or consume data that enhances other layers?

- Workflow Continuity: Does this exist in the same job context as our core, or does it require the customer to “change hats”?

- Switching Cost Multiplication: Does adding this make it meaningfully harder to leave the entire stack?

If it fails two of three tests, it’s not strategic adjacency—it’s distraction.

Where Adjacency Stacks Fail: The Cautionary Tales

The framework isn’t universally applicable. Three failure modes kill adjacency strategies:

Failure Mode 1: Forced Integration

GE’s attempt to build an industrial IoT platform (Predix) failed because it assumed owning jet engines, power turbines, and locomotives created natural stacking potential. The problem: each industrial vertical had unique data models, regulatory requirements, and customer workflows. The “stack” was actually five disconnected products force-bundled under a platform narrative. Customers bought GE turbines; they didn’t buy “GE’s industrial data ecosystem.”

Failure Mode 2: Misread Value Drivers

WeWork believed real estate was an adjacency stack opportunity: coworking, plus enterprise office management software (Powered by We), plus residential living (WeLive), plus education (WeGrow), plus… the vision went bankrupt. The error was assuming brand affinity (“We like WeWork’s aesthetic”) translated across categorically different purchase decisions (office space vs. housing vs. schools). Adjacency requires operational synergy, not just lifestyle branding.

Failure Mode 3: Underestimating Specialist Intensity

Salesforce’s attempt to stack marketing automation (Pardot/Marketing Cloud) on top of CRM worked. Their effort to stack CPQ (configure, price, quote) software succeeded. Their expansion into collaboration (Chatter, then Quip) failed spectacularly against Slack—until they just acquired Slack outright. The lesson: some adjacencies face incumbents with such deep specialization and passionate user bases that “good enough + integrated” loses to “excellent + standalone.” Know when to build, buy, or partner.

The Second-Order Implication: Markets Become Layer Games

Here’s what adjacency stacking reveals about the future of competition: markets are decomposing into layers, and the fight isn’t about winning categories—it’s about owning layers that multiply in value when combined.

Traditional strategy assumes you dominate a category (CRM, payments, cloud storage), then maybe expand into others. Adjacency stack dynamics flip this: you occupy a foundational layer, then systematically absorb adjacent layers until you’re not a “product company” but an infrastructure company that happens to offer products.

This creates a brutal dynamic for specialists. You can build the best X in the world, but if a stack player offers 85%-as-good X bundled with Y and Z at a combined price below your standalone X, you lose not on product merit but on workflow gravity. The strategic question shifts from “How do we build better features?” to “How do we survive in a world where our product is someone else’s feature?”

Three responses emerge:

Response 1: Out-Integrate Them — Become the best point solution and the easiest to integrate into every stack. Twilio survives in a world where AWS, Google, and Microsoft offer communications APIs because their developer experience and reliability make them the default choice even within competitors’ ecosystems.

Response 2: Find the Anti-Stack Niche — Serve customers who specifically don’t want bundled solutions. Roam Research, Notion alternatives, and other focused productivity tools win users fleeing all-in-one platforms. The anti-stack is a viable strategy—if you accept a smaller TAM.

Response 3: Build Your Own Counter-Stack — This only works if you can move faster than incumbents or serve a segment they ignore. Canva started as a simple design tool and later added presentations, video editing, websites, whiteboards, and print services. They’re building an anti-Adobe stack for non-designers.

The players who fail are those who optimize their core while pretending the stack game isn’t happening. That’s where Sarah Chen’s CRM company went wrong. They measured themselves against Salesforce on CRM metrics and came out on top. They lost the deal because Salesforce wasn’t selling CRM—they were selling surface area.

The Actionable Mandate: Stack or Be Stacked

If you’re a CEO, product leader, or strategist operating in any market with digital adjacencies, you face a binary choice: systematically build your adjacency stack or accept that someone else will make you a feature inside theirs.

This doesn’t mean reckless expansion. It means rigorous adjacency selection guided by the framework above: data synergy, workflow continuity, switching cost multiplication. It means shifting your strategy horizon from “How do we win this product category?” to “How do we become infrastructure?”

Start Monday morning by gathering your leadership team and asking three questions:

- What do our customers do in the 30 minutes before and after using our product? Map those activities.

- What proprietary data do we generate that would create an asymmetric advantage in adjacent capabilities? List them.

- If our biggest competitor launched a bundled version of our product plus two adjacencies tomorrow, which two would hurt us most? Prioritize those.

The adjacency stack isn’t a growth tactic. It’s the new logic of defensible competition. Markets don’t reward the best products anymore. They reward the most coherent, multiplying systems. Build yours before someone else makes you a feature.

Sources & Further Reading:

- Hamilton, Ben. “Platform Strategy and the Adjacency Advantage.” Harvard Business Review, 2022.

- Cusumano, Michael et al. “The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition.” HarperBusiness, 2019.

- Microsoft Investor Relations. “FY2024 Q4 Earnings: Commercial Cloud and Productivity Growth.” Microsoft.com, 2024.

- Chen, Andrew. “The Cold Start Problem: How to Start and Scale Network Effects.” Harper Business, 2021.

- Parker, Geoffrey et al. “Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy.” W.W. Norton, 2016.