The Applied Tech Radar: Filtering Hype for Strategic Implementation

Salesforce spent $27.7 billion acquiring Slack in 2021. Within 18 months, they’d written down hundreds of millions of dollars in value. Not because Slack was bad technology, it wasn’t. But because the strategic thesis (“we need to own workplace collaboration”) ignored a fundamental question: Does this technology solve a problem our customers actually have, or a problem we think they should have?

This pattern repeats across industries with numbing regularity. Retail giants pour resources into metaverse stores while their e-commerce checkout flow hemorrhages conversions. Banks launch blockchain pilots while their core banking systems can’t handle real-time fraud detection. Manufacturers pursue digital twin implementations even as their production lines still rely on clipboards.

The issue isn’t technological ignorance. Most large enterprises have CTOs who understand the tech stack. The problem is strategic blindness—the inability to separate signal from noise when emerging technologies arrive wrapped in billion-dollar valuations and breathless press coverage. Leaders know they can’t ignore innovation. But they also can’t chase every shiny object. What they lack is a systematic framework for deciding which emerging technologies deserve resources and which deserve polite disinterest.

Download the Artifacts:

Applied Tech Radar Scoring Tool

Tech Discard Log Template

The Applied Tech Radar System: From Hype to Strategic Clarity

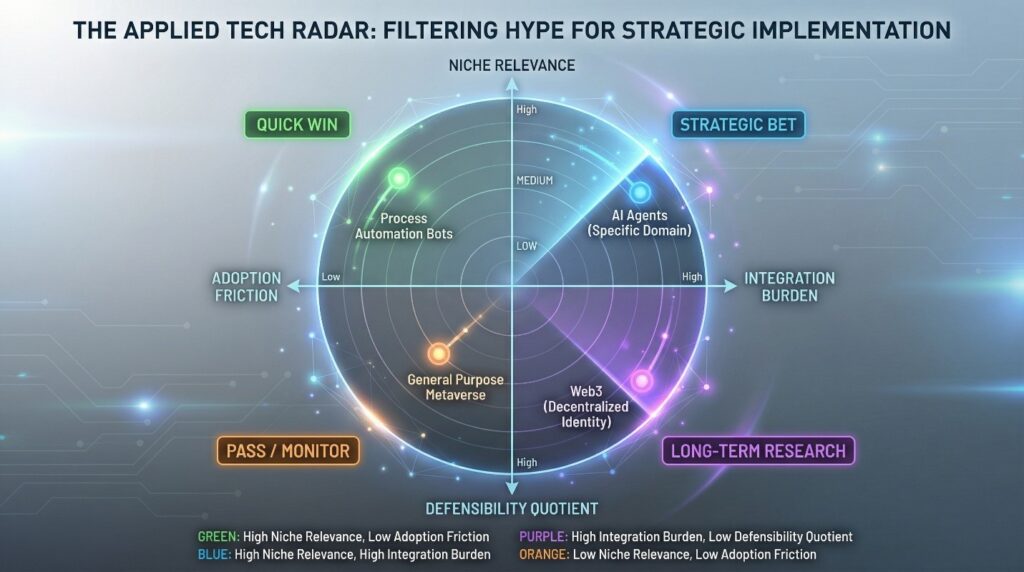

The Applied Tech Radar operates on two axes that cut through the fog of tech evangelism. The vertical axis measures Market Maturity versus Your Timing—the gap between when a technology becomes broadly viable and when your specific segment actually needs it. The horizontal axis tracks Strategic Fit versus Tactical Noise—whether this technology addresses a core constraint in your business model or merely automates a peripheral process.

These axes create four distinct quadrants, each demanding a radically different response.

Quadrant I: Strategic Accelerators (High Fit, Right Timing) This is where competitive advantage lives. Technologies here directly address your current strategic constraints, and the market infrastructure supports adoption. When Walmart implemented computer vision systems for inventory management in 2019, they weren’t chasing hype. They were solving a $3 billion shrinkage problem with technology that had finally matured beyond the research lab and into reliable, scalable deployment.

The signature of a Strategic Accelerator: it makes an existing capability dramatically better or cheaper, not hypothetically different. Netflix’s shift to AWS in the early 2010s wasn’t visionary futurism. It was recognizing that cloud infrastructure had matured to the point where they could scale streaming capacity faster and more cheaply than by building data centers. The technology matched their immediate constraint—unpredictable demand spikes—and the market timing was right.

Quadrant II: Premature Optimization (High Fit, Wrong Timing) These technologies will matter to your business—just not yet. The infrastructure isn’t ready. The talent pool is too thin. The vendor ecosystem is immature. Moving too early burns capital and organizational credibility.

Consider autonomous delivery vehicles. For logistics companies, the strategic fit is obvious: labor represents 50-60% of last-mile delivery costs. But in 2024, despite a decade of pilots, autonomous delivery remains trapped in geo-fenced experiments. Regulatory frameworks are incomplete. Edge cases—such as snow, construction, and aggressive drivers—still require human intervention. FedEx and UPS maintain pilot programs, but they’re not betting the farm on them. They’re maintaining optionality while the technology matures. That’s the correct response to Premature Optimization: watch closely, experiment cheaply, but don’t commit core resources.

Quadrant III: Tactical Enhancements (Low Fit, Right Timing). These technologies work. They’re readily available. They just don’t move your strategic needle. Adopting them won’t hurt you, the ROI might even be positive—but they won’t create differentiation. They’re process improvements, not transformations.

Robotic process automation is a good fit for most enterprises. It can automate repetitive back-office tasks with proven reliability. But it doesn’t change your competitive position. Your rivals have access to the same tools from the same vendors. The value is operational efficiency, not strategic advantage. Treat these technologies as you would any IT upgrade: evaluate ROI, implement if justified, move on. Don’t confuse them with strategic priorities.

Quadrant IV: Distraction Zone (Low Fit, Wrong Timing) This is where organizational discipline dies. These are technologies that generate enormous press coverage but have neither strategic relevance to your business nor sufficient market maturity to support reliable implementation. Yet they consume board meeting time and executive attention because someone asked, “What’s our Web3 strategy?”

The distraction zone is where most innovation theater happens. When Walmart and Disney announced metaverse initiatives in 2021-2022, they joined dozens of Fortune 500 companies in chasing a technology with no clear path to revenue in their core businesses. By late 2023, most had quietly shelved these projects. Not because the metaverse will never matter—it might—but because in 2024, for retail and entertainment companies, it solves no pressing constraint and the technology remains embryonic for mass-market applications.

Applying the Radar: Two Technologies, Radically Different Implications

Let’s test the framework against two technologies dominating current discourse: generative AI and blockchain-based supply chain tracking.

Generative AI: Location Determines Strategy

For a B2B software company selling to creative agencies, generative AI sits squarely in Quadrant I: Strategic Accelerator. The technology is production-ready. Major platforms (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google) offer stable APIs. The strategic fit is direct: their customers use these tools daily for content creation, and integration into existing products creates immediate differentiation. Canva’s integration of AI image generation didn’t require them to evangelize the technology—their users were already familiar with DALL-E and Midjourney. Canva just made it seamless within their workflow.

For a commercial real estate company, the same technology lands in Quadrant III: Tactical Enhancement. They might use AI to draft property descriptions or generate market reports. Useful? Sure. Strategic? No. Their competitive advantage rests on deal flow, relationships, and market knowledge—none of which AI fundamentally transforms. Implementing it is a reasonable productivity play, not a strategic imperative.

For a pharmaceutical manufacturer, generative AI is Quadrant II: Premature Optimization. The potential strategic fit is enormous—AI could accelerate drug discovery, predict protein folding, and optimize clinical trials. But in 2024, regulatory frameworks remain unclear. Liability for AI-generated research insights is undefined. The talent required to deploy these systems safely in regulated environments is scarce. Pfizer and Moderna maintain research partnerships, but they’re not restructuring R&D around AI outputs. They’re positioning for when the technology and its surrounding ecosystem mature.

Blockchain Supply Chain: Mostly Distraction

For most enterprises, blockchain-based supply chain tracking remains in Quadrant IV: Distraction Zone. The technology works—Walmart and Maersk have functional implementations. But ask the hard question: what problem does it solve that existing databases and EDI systems don’t?

The typical pitch: “Blockchain creates an immutable, transparent record of product movement.” True. But immutability only matters if you don’t trust your partners. For most supply chains, the problem isn’t participants lying about shipment data. It’s participants using incompatible systems, not sharing data due to competitive concerns, or making errors in manual data entry. Blockchain doesn’t fix those problems. Shared databases with API integrations do—and they’re vastly simpler and cheaper.

The exception: industries with genuine trust deficits and regulatory requirements for provenance. Diamond tracking through the Kimberley Process leverages blockchain’s immutability to create real value, as the entire system is designed to prevent conflict diamonds from entering legitimate supply chains. The technology maps to a specific, high-stakes trust problem. That moves it to Quadrant I for that specific use case.

For everyone else, the blockchain supply chain remains a solution seeking a problem—often implemented to signal innovation rather than solve constraints.

The Implementation Playbook: What to Do in Each Quadrant

Quadrant I – Strategic Accelerators: Move Fast. When a technology lands here, speed matters. Your competitors see the same opportunity. Build a 90-day implementation sprint. Assign your best product and engineering talent. Create direct executive ownership—not a committee. Accept that the first iterations will be imperfect. The goal is shipping a version that captures 60% of the value in three months, not engineering perfection in eighteen.

Warning sign: If you’re still conducting feasibility studies on a Strategic Accelerator technology six months after identifying it, you’ve already lost ground.

Quadrant II – Premature Optimization: Build Optionality. Don’t ignore these technologies. Don’t bet on them either. Instead:

- Maintain small, dedicated research teams that track developments

- Run time-boxed experiments with fixed budgets

- Develop relationships with leading vendors before they’re mainstream

- Train a core team so you can scale quickly when timing shifts

The mistake is either pretending the technology doesn’t exist or committing major resources before the ecosystem matures. Both extremes are wrong. The right response is disciplined observation with limited downside exposure.

Quadrant III – Tactical Enhancements: Standard IT Evaluation. Apply conventional ROI analysis. If the payback period is acceptable and the implementation risk is low, proceed. If not, skip it. Don’t dress these up as strategic initiatives. They’re operational improvements. Treat them as such.

Critical rule: Never let tactical enhancements consume strategic resources. A common failure pattern: the organization pours energy into implementing RPA across departments while a true Strategic Accelerator technology languishes in a pilot program because “we’re focused on automation right now.” That’s exactly backward.

Quadrant IV – Distraction Zone: Aggressive Filtering. This requires organizational courage. When board members ask about the company’s metaverse strategy, the correct answer might be: “We’ve evaluated it. It’s not strategically relevant to our business in the next three years. We’re monitoring developments, but we’re not allocating resources beyond that.”

Create a formal review process for technologies in this quadrant. Evaluate them annually—not quarterly. Resist the pressure to “do something” just to have a slide deck for the next board meeting.

The Dynamic Radar: Technologies Move Between Quadrants

A static assessment is worthless. Technologies migrate across quadrants as markets, and your business evolves.

Cloud computing moved from Quadrant II to Quadrant I for most enterprises between 2008 and 2012. In 2008, the technology worked, but the vendor ecosystem was thin, security concerns were unresolved, and enterprise-grade SLAs didn’t exist. By 2012, AWS had proven reliability at scale, a robust partner network had emerged, and the cost advantages were undeniable. Companies that moved in 2009 overpaid for risk. Companies that waited until 2014 overpaid in lost efficiency.

Your job is recognizing inflection points. Set triggers for re-evaluation:

- Regulatory clarity emerges or disappears

- Dominant vendors achieve certain adoption milestones

- Your strategic constraints shift due to market changes

- Adjacent technologies mature and create compound opportunities

Amazon’s acquisition of Kiva Systems (warehouse robotics) in 2012 for $775 million looked like Quadrant II—right fit, early timing. But Amazon correctly predicted that e-commerce growth would create warehouse labor constraints faster than competitors anticipated. By the time rivals like Walmart realized robotics had shifted to Quadrant I, Amazon had a six-year head start and had stopped selling Kiva systems externally. The timing assessment was aggressive but correct.

The Organizational Discipline to Execute This Framework

Knowing the quadrants is easy. Acting on them is hard because organizations have structural antibodies against this kind of clarity.

Innovation teams are incentivized to pursue novelty. They pitch Quadrant IV technologies because they’re exciting and generate conference speaking opportunities. Business units advocate for Quadrant III technologies because they make their operational lives easier. Meanwhile, Quadrant I opportunities sit in pilot purgatory because they require cross-functional coordination and executive risk-taking.

You need forcing mechanisms:

Annual Technology Portfolio Review: Once per year, map every significant technology initiative to the quadrant framework. Kill everything in Quadrant IV that’s consuming more than monitoring-level resources. Accelerate everything in Quadrant I. This sounds obvious. In practice, it requires overcoming departmental politics and sunk-cost fallacies.

Explicit Resource Allocation: Declare that 70% of innovation resources go to Quadrant I, 20% to Quadrant II, 10% to Quadrant III, and 0% to Quadrant IV beyond monitoring. Force teams to defend why their project deserves its quadrant classification. The conversation that emerges—”Why do you believe this is Strategic Accelerator versus Premature Optimization?”—is more valuable than the final classification.

Executive Ownership of Quadrant I: Strategic Accelerators don’t belong in innovation labs. They belong on executive scorecards. If a technology genuinely moves your strategic needle and the timing is right, the CEO or business unit president should own the outcome. Innovation theater happens when transformational technologies are delegated to people without P&L authority.

The Contrarian Truth: Most Technologies Don’t Matter to Most Companies

Here’s what this framework reveals: for any given company, at any given time, most emerging technologies are genuinely irrelevant. This isn’t defeatism or conservatism. It’s strategic focus.

The tyranny of tech media is the implicit assumption that every technology matters to every company. It doesn’t. Web3 might be transformational for digital identity systems. It’s probably irrelevant to industrial manufacturing. Computer vision is strategic for autonomous vehicles. It’s tactical for retail analytics. Generative AI rewrites content creation. It barely touches commercial construction.

The competitive advantage doesn’t come from adopting every technology. It comes from adopting the right technologies with the right timing and ignoring the rest with disciplined indifference.

When Microsoft’s Satya Nadella bet the company’s future on cloud and AI while de-emphasizing consumer hardware, he wasn’t hedging. He was making an explicit quadrant assessment: Azure and AI tools were Strategic Accelerators for Microsoft’s enterprise business. Consumer devices were, at best, Tactical Enhancements. He concentrated resources accordingly. The result: Microsoft’s market cap grew from $300 billion in 2014 to over $3 trillion in 2024.

That clarity—knowing what not to do as clearly as what to do—is the framework’s ultimate value. It transforms the question from “What’s our strategy for this technology?” to “Does this technology deserve a strategy?”

Most of the time, the answer is no. And that’s exactly right.

Sources & Further Reading:

- Walmart Annual Reports (2019-2023), detailing computer vision implementation and shrinkage reduction metrics

- “The Everything Store” by Brad Stone – Netflix AWS migration case study and strategic decision-making process

- McKinsey & Company, “Blockchain beyond the hype: What is the strategic business value?” (2023)

- Gartner Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies (2020-2024), tracking technology maturity and adoption curves

- Harvard Business Review, “Why So Many High-Profile Digital Transformations Fail” (2023), analyzing enterprise technology adoption patterns.