The Asymmetric Strategy Canvas: How to Turn Incumbent Weaknesses into Your Competitive Moat

Three weeks after launching its cloud storage service for creative professionals in 2015, Frame.io’s founder Emery Wells noticed something unexpected. Adobe users weren’t just adopting Frame.io—they were actively hiding it from their IT departments. They’d expense it as “software licenses” or bury it in miscellaneous costs. Wells had stumbled onto what military strategists call an asymmetric advantage: he’d found a battle the incumbent giant couldn’t fight without undermining its own fortress.

This wasn’t luck. Wells had identified a structural blind spot—Adobe’s enterprise sales model made it impossible to serve agile creative teams who needed instant collaboration without IT approval cycles. The larger Adobe grew, the more vulnerable this flank became. Frame.io was sold to Adobe in 2021 for $1.275 billion.

Most strategy frameworks fixate on what you should build. The Asymmetric Strategy Canvas does something more surgical: it maps where entrenched competitors cannot respond, even when they see you coming. This is about exploiting the antibodies inside successful companies—the very mechanisms that made them dominant now prevent them from defending certain territory.

Download the Artifacts:

Blind Spot Validation Interview Guide

Asymmetric Value Curve Worksheet

The Incumbent’s Invisible Cage

Large companies don’t fail because they’re stupid or lazy. They fail because success creates ossification. Every market leader is trapped by three structural constraints that smaller players can weaponize:

Revenue Architecture Lock-In. When Salesforce initially dismissed Slack’s enterprise growth, it wasn’t arrogance—it was math. Salesforce’s average contract value ran $50,000-$300,000 with 12-18 month sales cycles. Slack was landing teams at $800/month with same-day activation. For Salesforce to chase that segment meant restructuring comp plans, retraining sales teams, and cannibalizing partner channels. The corporate antibodies rejected it until Slack reached $900M in ARR. By then, defense required a $27.7 billion acquisition.

Customer Promise Handcuffs. Oracle’s database business exemplifies this trap. Their enterprise customers pay premium prices for absolute reliability, backward compatibility, and 24/7 support. When cloud-native databases like MongoDB offered 10x faster development cycles, Oracle couldn’t simply match it—their existing customers were paying specifically for the stability that came from slow, deliberate releases. Speed was a liability in their value equation. MongoDB found $7.9 billion in market cap in that contradiction.

Organizational Scar Tissue. Microsoft’s delayed response to cloud computing wasn’t about missing the trend—they saw it clearly. The problem was Windows Server revenue ($20B+ annually) and the careers of 40,000+ people built around on-premise software. AWS had no such baggage. When Andy Jassy proposed EC2, there was no existing business to defend, no channel partners to appease, no sales force whose compensation depended on perpetual licenses. Amazon’s lack of scar tissue was the asymmetry.

These aren’t temporary conditions. They’re permanent features of success at scale.

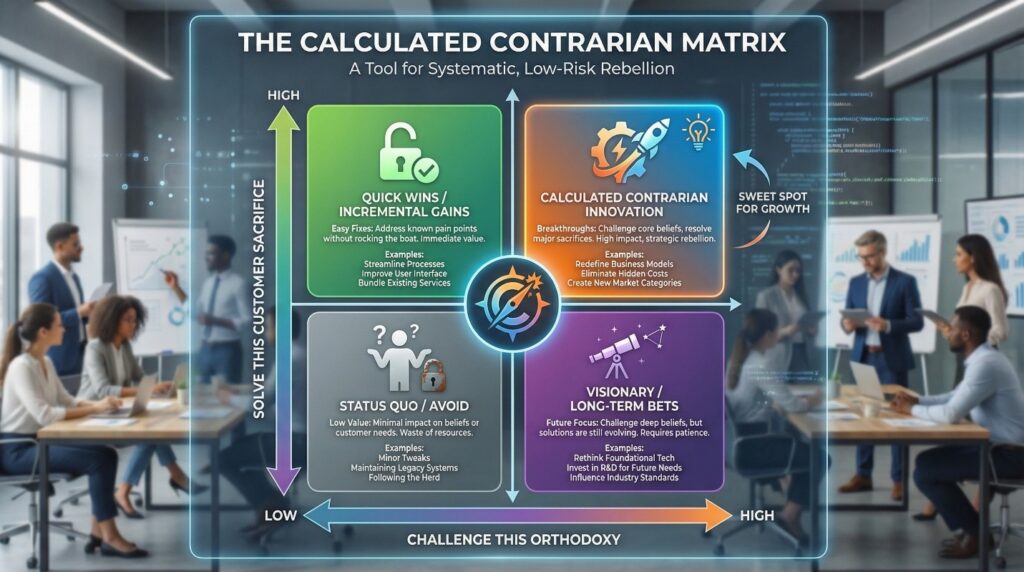

The Asymmetric Strategy Canvas Explained

The Canvas operates on two axes. The vertical axis measures Incumbent Investment Intensity—how deeply the dominant player has committed capital, identity, and organizational structure to a particular approach. The horizontal axis tracks Market Evolution Velocity—how rapidly customer needs, technology, or economics are shifting in a specific dimension.

This creates four strategic zones:

The Fortified Core (High Investment, Low Evolution): Here, incumbents are unbeatable. Enterprise ERP systems, core banking infrastructure, and SWIFT network protocols. Don’t attack directly. These are moats, not blind spots.

The Efficient Frontier (High Investment, High Evolution): The incumbent is heavily invested, but the ground is shifting. This is where they’re most dangerous—they’ll fight viciously because they must. Think Google defending search against AI-powered alternatives. They have the resources and the existential motivation. Tread carefully.

The Ignored Adjacent (Low Investment, Low Evolution): Unglamorous, stable markets the incumbent has consciously deprioritized. Sometimes viable for boutique plays, but limited upside. Industrial maintenance software, niche compliance tools. The incumbent doesn’t care enough to crush you, but the market doesn’t care enough to make you huge.

The Asymmetric Opportunity (Low Investment, High Evolution): This is the kill zone. The market is moving fast, but the incumbent has minimal structural commitment to the old approach, which paradoxically prevents them from pivoting quickly. Their lack of investment becomes strategic paralysis because they can’t justify major resource reallocation to an unproven shift.

The magic happens when you identify segments where:

- Customer needs are evolving faster than the incumbent can organizationally respond

- The incumbent’s business model makes the “correct” response economically irrational

- The incumbent’s brand promise prevents them from making the necessary trade-offs

Mapping Your Attack Vector: A Practical Framework

Start by deconstructing the incumbent’s value chain into discrete components. For each component, ask three questions:

Question 1: What is the incumbent optimizing for that customers are starting to deprioritize?

When Zoom entered the video conferencing market in 2013, Cisco WebEx was optimizing for IT administrator control—SSO integration, centralized management, and audit logs. But the buying decision had shifted to end users who valued “click, and it works” over administrative control. Cisco couldn’t reorient without alienating the CIOs who approved six-figure contracts. Zoom captured meeting hosts, then forced IT to capitulate. By 2019, Zoom had 50.4% of the market; Cisco had fallen to 9.8%.

Question 2: Where is the incumbent’s cost structure preventing competitive pricing in emerging segments?

Toast attacked the restaurant POS market despite Square and traditional POS providers. Legacy POS companies had field service teams—technicians who’d physically install and maintain systems. Toast was built cloud-first with remote support. When restaurants wanted to add delivery integration or online ordering during COVID-19, Toast could bundle it at marginal cost. Legacy providers needed new hardware, truck rolls, and 48-hour installation windows. Toast now processes $127 billion in gross payment volume because its competitors’ cost structure was its prison.

Question 3: What customer segment is too small or too weird for the incumbent’s sales motion but large enough for you to build a business?

Roam Research identified a blind spot in the productivity software market. Microsoft and Google optimized for organizational collaboration—shared documents, version control, and permission hierarchies. But there was a segment of knowledge workers who thought in networks, not hierarchies. Researchers, writers, strategists. Too small for Microsoft to build a dedicated product line. Too strange for their existing UI paradigms (backlinking and bi-directional linking violated document-centric metaphors). Roam carved out a devoted user base willing to pay $15/month. The incumbent’s sales model—which required products to address 10M+ users to justify development—was the barrier.

The Second-Order Calculus: When Incumbents Can’t Respond

The deepest asymmetries emerge when your attack forces the incumbent into a zugzwang—any move they make worsens their position.

The Dollar Shave Club Paradox. When DSC launched in 2011 with $1 razors delivered by mail, Gillette faced a brutal choice. Lower prices on their flagship Fusion razors (which commanded $3-$4 per cartridge) would destroy category profitability—Gillette owned 70% market share, so a price cut would cannibalize billions in margin. But ignoring DSC meant ceding the fastest-growing customer acquisition channel (DTC subscription) to a competitor. Gillette tried fighting with their own subscription service in 2015, but it undermined retail partnerships that still drove 90% of revenue. Unilever acquired DSC for $1 billion in 2016. Gillette’s market share dropped from 70% to 54% by 2020.

The lesson: DSC didn’t need to beat Gillette on product quality. They needed to make Gillette’s optimal response a choice between bad and worse.

The Netflix-Blockbuster Non-Battle. Blockbuster’s business model wasn’t just retail stores—it was late fees. In 2000, late fees generated $800 million of Blockbuster’s revenue, roughly 16% of total. When Netflix offered no-late-fee DVD-by-mail, Blockbuster couldn’t simply eliminate late fees without immediately cutting revenue by double digits and tanking their stock price. They tried launching Blockbuster Online in 2004, but it was structurally compromised—to protect retail stores, they limited online selection and gave preferential treatment to in-store exchanges. The core business model was the cage. Netflix didn’t out-compete Blockbuster; they designed a business that Blockbuster couldn’t respond to without self-destruction.

Implementation Protocol: Building Your Canvas

Here’s your Monday morning process:

Step 1: Map the Incumbent’s Commitments (The Gravity Well)

Create a spreadsheet. Columns: Business Unit | Revenue Contribution | Key Metrics | Organizational Headcount | Strategic Narrative (what they tell investors).

This reveals what they must defend. AWS had to defend compute infrastructure—it was 60%+ of revenue. They were vulnerable in specialized databases. Sure enough, specialized database companies (Snowflake, Databricks, MongoDB) captured $100B+ in combined enterprise value by targeting workloads AWS treated as generic.

Step 2: Identify the Evolution Vectors

For each major customer need in the value chain, rate the velocity of change (1-10 scale). What’s moving fast?

- Technology enablement (new capabilities)?

- Customer preferences (generational, economic, social)?

- Regulatory environment?

- Channel dynamics (how customers buy)?

Zoom identified that video quality (technology) was accelerating, but the buying process (channel) was shifting even faster—from IT procurement to individual team adoption.

Step 3: Plot the Opportunity Matrix

For each component: High Incumbent Investment + High Evolution = Fortified but moving (dangerous fight). Low Incumbent Investment + High Evolution = Asymmetric opportunity.

Your targets are components where evolution velocity outpaces incumbent adaptability, AND where the incumbent’s org structure prevents rapid response.

Step 4: Validate the Zugzwang

For your identified opportunity, war-game the incumbent’s response options:

- If they match your approach, what do they sacrifice? (Revenue, brand, channel, existing customers?)

- If they acquire a competitor, does it conflict with existing product lines?

- If they build a skunkworks, can they ring-fence it from corporate antibodies?

If all paths hurt them, you’ve found asymmetry.

Step 5: Design for Escalation Dominance

Your strategy should get stronger as the incumbent’s response intensifies.

When Tesla faced traditional automakers, they didn’t just build electric cars—they built a vertically integrated manufacturing model that got more efficient with scale, while traditional manufacturers’ dealer networks and multi-brand strategies became liabilities in an EV world. The more Ford invested in Mustang Mach-E, the more tension there was with their dealer network. Tesla had no dealers to protect.

Pitfalls and Misapplications

Pitfall 1: Confusing Neglect with Structural Inability.

Just because an incumbent isn’t serving a segment doesn’t mean they can’t. Slack thought enterprises were too complex for synchronous chat. Microsoft proved otherwise with Teams—they had the distribution (bundled with Office 365), enterprise relationships, and compliance infrastructure. Slack misread Microsoft’s choice not to prioritize chat as an inability to respond. Microsoft flipped the switch when the threat became clear.

Pitfall 2: Overestimating Organizational Inertia.

Incumbents are slow until they’re not. When Google faced an existential AI threat from ChatGPT, they reorganized Bard development in 90 days and launched it publicly. The antibodies disappear when the corporate immune system perceives the threat as terminal. Your asymmetry is a time-bound window, not a permanent moat.

Pitfall 3: Building a Feature, Not a Business Model Mismatch.

The asymmetry must be structural, not tactical. If the incumbent can copy your feature set without undermining their core business, you don’t have asymmetry—you have a temporary head start. Snapchat’s Stories feature was brilliant, but Instagram could replicate it without business model conflict. Snapchat’s market cap peaked at $28 billion and fell to $16 billion as Instagram Stories surpassed it. Contrast with WhatsApp—Facebook couldn’t replicate WhatsApp’s business model (no ads, privacy-first) without contradicting Facebook’s surveillance advertising model. That’s structural asymmetry. Facebook paid $19 billion rather than compete.

Thinking Beyond

The Asymmetric Strategy Canvas reveals an uncomfortable truth about competition: your advantage isn’t primarily about what you do better—it’s about identifying what the incumbent cannot do at all without violating the organizational logic that made them successful.

This inverts conventional strategy. You’re not trying to beat them at their game. You’re changing the game to one where their strengths become weaknesses, where their assets become liabilities, and where their organizational muscle memory becomes paralysis.

The deepest strategic question isn’t “What can we do that they can’t?” It’s “What would destroy them to even try?”

This is why disruption feels incomprehensible from inside large organizations. The threat isn’t someone doing the same thing better. It’s someone succeeding by violating the assumptions that define success in your organization. When you price at 10% of the incumbent’s offering, you’re not competing on price—you’re attacking the cost structure that funds their entire organization. When you serve customers they deem “too small,” you’re not finding an overlooked niche—you’re exploiting a sales model that requires deals above a certain size to justify the cost of pursuit.

The Asymmetric Strategy Canvas doesn’t promise easy victories. What it does is direct your scarce resources toward the handful of battles where the incumbent’s competitive response is structurally compromised, where every dollar they spend defending makes them weaker, where their board won’t let them fight the way they need to.

That’s not just strategy. That’s the geometry of inevitability.

The question isn’t whether giants can be beaten. It’s whether you can identify the precise angle where their armor has gaps that they cannot close without removing the armor entirely. Find that angle, and you’re not fighting them—you’re forcing them to fight themselves.

That’s an asymmetry worth building a company around.

Sources & Further Reading

- Frame.io acquisition details and creative workflow market analysis: TechCrunch, “Adobe to Acquire Frame.io for $1.275 Billion” (August 2021)

- Salesforce/Slack market dynamics and enterprise collaboration evolution: Slack S-1 filing (2019); Bessemer Venture Partners “State of the Cloud” reports (2018-2020)

- MongoDB vs. Oracle database market positioning and cloud-native database adoption: MongoDB financial disclosures (2020-2023); Gartner “Magic Quadrant for Cloud Database Management Systems.”

- Zoom vs. Cisco WebEx market share data: Okta “Businesses @ Work” report (2019); Synergy Research Group enterprise communications market analysis

- Dollar Shave Club/Gillette razor market dynamics: Unilever acquisition announcement (2016); Euromonitor International razor market share data (2010-2020)